Background: Historical views of mental illness, defining abnormality, categorising mental disorders

Key Study: Rosenhan (1973) On being sane in insane places

Application / Strategy: Characteristics of an affective disorder, a psychotic disorder and an anxiety disorder

Key Study: Rosenhan (1973) On being sane in insane places

Application / Strategy: Characteristics of an affective disorder, a psychotic disorder and an anxiety disorder

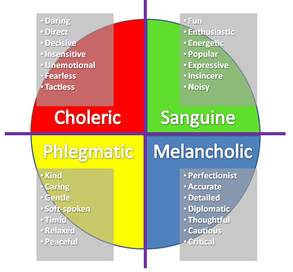

The 4 Humours

The 4 Humours

Background: Historical Views of Mental Illness

Over time, there have been lots of views about the cause of mental illness, such as:

Over time, there have been lots of views about the cause of mental illness, such as:

- Demons / evil spirits

- An imbalance in the 4 humours (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) inside the person’s body

- Witchcraft

- The unconscious mind

- Maladaptive thinking processes

- An imbalance in brain chemicals

- Too much or too little brain activity

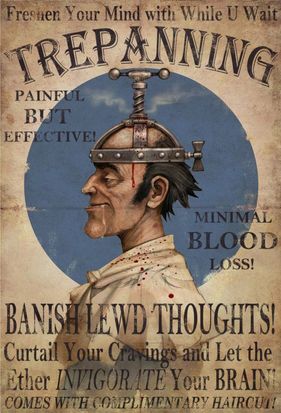

Whatever a person believes CAUSES mental illness will determine HOW it is treated. If you believed that the cause of mental illness was …., then the treatment would be:

- Demons / evil spirits - - - to get rid of the demons by trepanning (drilling holes in a person’s skull) / exorcism.

- An imbalance in the humours - - - to adjust the levels of the humours by using herbs / bloodletting.

- Witchcraft - - - to get rid of the witchcraft by burning them at the stake.

- The unconscious mind - - - to reveal what the unconscious is feeling by using the techniques of psychoanalysis (dream analysis, Rorschach inkblots, free association, etc.)

- Maladaptive thinking processes - - - to get rid of and adjust the thought processes by using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy.

- An imbalance in brain chemicals - - - to adjust the levels of the chemicals by using medication

- Too much or too little brain activity - - - to adjust activity of the brain by using ECT (electro-convulsive therapy) / psychosurgery.

Statistical Infrequency

Statistical Infrequency

Background: The Definitions of Abnormality

The term ‘abnormal’ literally means ‘not normal or usual’. One problem with defining abnormality is that there is no a single characteristic that applies to all ‘abnormality’. Also, defining psychological abnormality has ethical, practical and personal consequences for the person who is given that label.

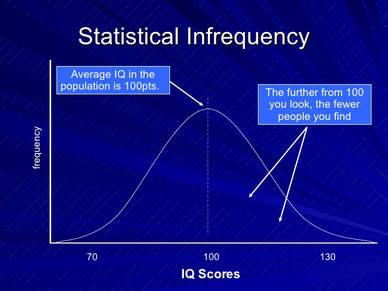

Definition #1: Statistical Infrequency

When a person has a characteristic less common than most of the population e.g. being more depressed or having lower intelligence. This uses the standard deviation and distribution.

Evaluation points

Definition #2: Deviation from social norms

Abnormal behaviour is a deviation from written (explicit) and unwritten (implicit) rules about how one ‘ought’ to behave. Any behaviour which breaks these social rules (such as decency, politeness, violence) is considered as undesirable and therefore abnormal by the rest of the group.

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

The term ‘abnormal’ literally means ‘not normal or usual’. One problem with defining abnormality is that there is no a single characteristic that applies to all ‘abnormality’. Also, defining psychological abnormality has ethical, practical and personal consequences for the person who is given that label.

Definition #1: Statistical Infrequency

When a person has a characteristic less common than most of the population e.g. being more depressed or having lower intelligence. This uses the standard deviation and distribution.

Evaluation points

- Real life application – Strength Statistical deviation is a useful part of clinical diagnosis so it therefore applicable to real life – e.g. the IQ distribution is a representative of the real population – in fact, most disorders have some sort of statistical measurement.

- Unusual characteristics could be positive! Statistical deviation is useless when the “abnormality” is a good thing e.g. an IQ of 130! This is statistically abnormal but not clinically a bad thing!

- Labelling – does not always benefit the individual Labelling is powerful and might affect people in a negative way. If you give people a label, they might start acting in a way that fulfils the label.

- Some people are “abnormal” but lead happy and fulfilled lives. If we label someone then we run the risk of developing a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Definition #2: Deviation from social norms

Abnormal behaviour is a deviation from written (explicit) and unwritten (implicit) rules about how one ‘ought’ to behave. Any behaviour which breaks these social rules (such as decency, politeness, violence) is considered as undesirable and therefore abnormal by the rest of the group.

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

- Deviance is related to context (where you are) and degree (how much). Some behaviours are acceptable in one context but not another. There is also no clear line between what is abnormal deviation and eccentricity.

- Susceptible to abuse Szasz (1974) explained that when we refer to what the majority in a society thinks is normal, we may end up labelling behaviour as abnormal and labelling people with a mental illness when they are just a non-conformist.

- Cultural Relativism: Any attempt to define a person’s behaviour is silly without looking at the culture. What is considered abnormal in one culture may be considered to be acceptable in another.

Marie Jahoda

Marie Jahoda

Definition #3: Deviation from ideal mental health

Abnormality is seen as deviating from an ideal of positive mental health. This includes a positive attitude towards the self and an accurate perception of reality.

Jahoda identified 6 characteristics of ideal mental health:

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

Abnormality is seen as deviating from an ideal of positive mental health. This includes a positive attitude towards the self and an accurate perception of reality.

Jahoda identified 6 characteristics of ideal mental health:

- Positive attitudes towards the self

- Self-actualisation of one’s potential

- Resistance to stress

- Personal autonomy

- Accurate perception of reality

- Adapting to and mastering the environment

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

- Who can achieve all of this? How many do you have to lack before you would be judged as abnormal?

- Mental health is not the same as physical health. Doctors often use checklists to diagnose illness. This cannot be done for mental illness.

- Cultural Relativism: Most of these cannot be applied to other cultures – e.g. one culture may believe in ghosts, whereas another may see this as lacking an accurate perception of reality.

Failure to function adequately

Failure to function adequately

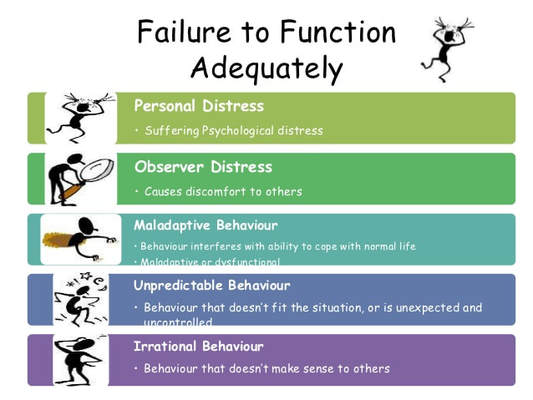

Definition #4: Failure to function adequately

If behaviour interferes with basic and daily functioning, it may be considered abnormal. Rosenhan and Seligman (1989) identified 7 features (characteristics) of behaviour that could be seen as ‘symptoms’ of abnormality. If 1 is observed, then it is unlikely that the label ‘abnormal’ would be used. If several are seen, then it is more likely that the person will be judged to be abnormal.

7 characteristics of failure to function adequately:

Evaluation Points: Weaknesses

If behaviour interferes with basic and daily functioning, it may be considered abnormal. Rosenhan and Seligman (1989) identified 7 features (characteristics) of behaviour that could be seen as ‘symptoms’ of abnormality. If 1 is observed, then it is unlikely that the label ‘abnormal’ would be used. If several are seen, then it is more likely that the person will be judged to be abnormal.

7 characteristics of failure to function adequately:

- Suffering

- Maladaptiveness (danger to self)

- Vividness & unconventionality (stands out)

- Unpredictably & loss of control

- Irrationality/incomprehensibility

- Causes observer discomfort

- Violates moral/social standards

Evaluation Points: Weaknesses

- The problem with this definition is that it is extremely subjective. What is functioning adequately or inadequately is a judgement and is different for each person– which person has the right to judge? People may be forced to receive help for unusual rather than abnormal behaviour.

- People may not be able to recognise that they are functioning inadequately or that they have a problem (such as personality disorders). Therefore, someone else has to define them as abnormal, such as a doctor or a judge, and this is controversial.

- Failure may be caused by other things apart from abnormality, such as ethnicity. Immigrants, for example, may be under extreme stress as they have problems with language, cultural differences, prejudices and it not always abnormality or mental disorders that cause inadequate functioning.

DSM-V

DSM-V

Background: Categorising Mental Illness

Classification of mental disorder involves taking sets of symptoms and putting them into categories. Once there is a set of abnormal symptoms classified into disorders, psychiatrist can diagnose individuals by looking at their symptoms and checking which disorder best fits those symptoms. This relies on self-reports from the patients.

There are 2 ‘tools’ used for the diagnosis of mental illness. These are the DSM – V and ICD – 10.

Evaluation points: Strengths

Evaluation points: Reliability

Evaluation points: Validity

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

Classification of mental disorder involves taking sets of symptoms and putting them into categories. Once there is a set of abnormal symptoms classified into disorders, psychiatrist can diagnose individuals by looking at their symptoms and checking which disorder best fits those symptoms. This relies on self-reports from the patients.

There are 2 ‘tools’ used for the diagnosis of mental illness. These are the DSM – V and ICD – 10.

- The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-V) is produced by the American Psychiatric Association. Krimsky and Cosgrove (2012) found that 69% of the panel working on the DSM-5 had links with the pharmaceutical industry.

- The International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD) is produced by the World Health Organisation.

Evaluation points: Strengths

- Helps to establish as reliable way to categorise and diagnose behaviours

- Helps to direct the most appropriate treatment for the individual

- Helps the patient realise why they are different and gives them and this can be a relief to have this label.

Evaluation points: Reliability

- Reliability means consistency. A system is reliable if people using it consistently arrive at the same diagnoses.

- One way of seeing how reliable a diagnosis is, is by testing whether different psychologists agree on the same diagnosis for the same patient (called inter rater reliability).

- Another way to assess reliability is to assess the same patients two or more times and see whether they consistently receive the same diagnosis (test – retest reliability).

Evaluation points: Validity

- Validity = the extent to which something measures what it set out to measure.

- One way to measure validity is to see if our system identifies a condition that will respond to a particular treatment (predictive validity).

- Another way to measure validity is to see if the diagnosis made one way agrees with the diagnosis made a different way (criterion validity).

- Validity is questioned if symptoms are very similar to those of another condition or if two conditions regular occur together (construct validity).

Evaluation points: Weaknesses

- Highly subjective – can change from one health professional to the next

- Requires self-report from individuals who may not realise that their behaviour as abnormal, or who may lie, have disordered thoughts and social desirability

- There is significant overlap between disorders e.g. loss of pleasure is a factor in depression and schizophrenia, whilst bipolar disorders and schizophrenia can feature delusions and disordered actions.

- Ethnocentrism –the culture can influence what is seen as abnormal. Some cultures may see behaviours as normal (like hearing God speak to them) whereas others would not.

- Aetiological validity – means the extent to which the cause of the disorder is the same for each patient. There may be a different cause of a disorder for different people.

|

Assessing the reliability and validity of the diagnosis of mental illness homework

Student essay plans can be found here |

Hodder Education's

Psychology Review Centre Spread on the Definitions of Abnormality can be found here |

| ||||||

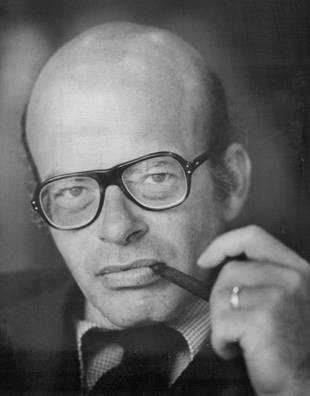

David Rosenhan

David Rosenhan

Key Study: Rosenhan (1973) On being sane in insane places

Background and aim

Rosenhan investigated the question: Can we tell the sane from the insane?

Based on this, the study had three aims:

1. To build on the work of previous researchers who had submitted themselves to psychiatric hospitalisation but only for a short period and often with the knowledge of hospital staff.

2. To test the reliability and validity of diagnostic systems (DSM II used at the time of the study)

3. To observe and report on the experience of being a patient in a psychiatric hospital.

Method

This is a field study in which Rosenhan uses a field experiment, participant observation and self-report.

Sample

Eight sane people (five men, three women) who consisted of a psychology graduate in his 20’s, three psychologists, a paediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter and a housewife were the participants.

Procedure

These pseudo-patients telephoned the hospital for an appointment, and arrived complaining of hearing voices. The voice was unfamiliar and the same sex as themselves, was often unclear but it said 'empty', 'hollow', 'thud'.

They gave a false name and job, but all other details given were true including relationships and events of life history. After admittance to the psychiatric ward, the pseudo patients no longer simulated any symptoms although they did display nervousness.

They took part in ward activities and when staff asked how they felt they reported feeling fine and were no longer experiencing symptoms. They were told they would have to get out of the hospital by convincing staff they were sane.

Pseudopatients secretly made notes about their observations; however, this became more open as staff didn’t seem bothered about this behaviour. In four out of the twelve hospitals observations of staff behaviour towards patients were carried out.

The pseudo-patients approached a staff member with the following request: 'Pardon me, Mr/Mrs/Dr X, could you tell me when I will be presented at the staff meeting?' or ‘When am I likely to be discharged?’

Results

Staff at a research and teaching hospital were surprised at the results and doubted that sane people could be admitted to their hospital. They were warned that one or more pseudo-patients would present themselves over the next three months attempting to be admitted - None actually did so.

Staff were asked to rate on a 10 point scale each patient according to the likelihood they were a pseudo- patient. Despite not having any mental illness, all of the pseudo-patients were admitted to the hospitals, with stays ranging from 8 to 52 days, with a mean stay of 19 days. 7/8 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and the eight with manic-depressive psychosis.

When they were discharged the label of ‘schizophrenia in remission’ was given. Their note taking was assumed to be a symptom or their illness - ‘Patient engages in writing behaviour’- while walking the corridors due to boredom was classified as anxiety.

Furthermore, distress from the pseudo-patients was not thought to be due to the situation, but a symptom of their illness. There is a great overlap between normal and abnormal behaviour, but once someone has being labelled as mentally ill, behaviour is interpreted differently.

35 out of 118 of the real patients actually thought that the pseudo-patients were fake and made comments such as - ‘You’re not crazy, you’re a journalist or a professor. You’re checking up on the hospital.’ During their collective stays in hospital 2100 pills were given to the pseudo-patients, with all but two being flushed down the toilet, which went unnoticed. Staff preferred to stay away from the patients - attendants spent an average of 11.3% of their time outside the ‘cage’ (the nickname for staff quarters).

Nurses left the cage 11.5 times per day and 9.4 times per night shift, with doctors only doing so 6.7 times a day on average. Patients’ movements were watched and restricted, their quarters and possessions could be entered and examined by any staff member and notes were available to all members of staff.

There was little personal privacy - some hospitals had no toilet doors, and examinations took place in semi-public rooms. There were also cases of serious physical abuse to patients but these abuses of power stopped in front of other staff. All pseudo-patients reported powerlessness and depersonalisation.

When the pseudo-patients made the request to staff a question the response was either brief while they were ‘on the move’, with head averted, or no response was given at all and staff rarely made eye contact with them. Pseudo-patients were spoken to 4% of the time by a doctor and 0.5% by a nurse, compared to 100% of students in the control group. Interestingly when the student asked where she could find a psychiatrist the response dropped to 78%.

In the follow up experiment, 41 out of 193 patients were judged with high confidence to be pseudo-patients by at least one member of staff, while 23 were judged to be by at least one psychiatrist and 19 by one psychiatrist and one other staff member.

Conclusions

Background and aim

Rosenhan investigated the question: Can we tell the sane from the insane?

Based on this, the study had three aims:

1. To build on the work of previous researchers who had submitted themselves to psychiatric hospitalisation but only for a short period and often with the knowledge of hospital staff.

2. To test the reliability and validity of diagnostic systems (DSM II used at the time of the study)

3. To observe and report on the experience of being a patient in a psychiatric hospital.

Method

This is a field study in which Rosenhan uses a field experiment, participant observation and self-report.

Sample

Eight sane people (five men, three women) who consisted of a psychology graduate in his 20’s, three psychologists, a paediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter and a housewife were the participants.

Procedure

These pseudo-patients telephoned the hospital for an appointment, and arrived complaining of hearing voices. The voice was unfamiliar and the same sex as themselves, was often unclear but it said 'empty', 'hollow', 'thud'.

They gave a false name and job, but all other details given were true including relationships and events of life history. After admittance to the psychiatric ward, the pseudo patients no longer simulated any symptoms although they did display nervousness.

They took part in ward activities and when staff asked how they felt they reported feeling fine and were no longer experiencing symptoms. They were told they would have to get out of the hospital by convincing staff they were sane.

Pseudopatients secretly made notes about their observations; however, this became more open as staff didn’t seem bothered about this behaviour. In four out of the twelve hospitals observations of staff behaviour towards patients were carried out.

The pseudo-patients approached a staff member with the following request: 'Pardon me, Mr/Mrs/Dr X, could you tell me when I will be presented at the staff meeting?' or ‘When am I likely to be discharged?’

Results

Staff at a research and teaching hospital were surprised at the results and doubted that sane people could be admitted to their hospital. They were warned that one or more pseudo-patients would present themselves over the next three months attempting to be admitted - None actually did so.

Staff were asked to rate on a 10 point scale each patient according to the likelihood they were a pseudo- patient. Despite not having any mental illness, all of the pseudo-patients were admitted to the hospitals, with stays ranging from 8 to 52 days, with a mean stay of 19 days. 7/8 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and the eight with manic-depressive psychosis.

When they were discharged the label of ‘schizophrenia in remission’ was given. Their note taking was assumed to be a symptom or their illness - ‘Patient engages in writing behaviour’- while walking the corridors due to boredom was classified as anxiety.

Furthermore, distress from the pseudo-patients was not thought to be due to the situation, but a symptom of their illness. There is a great overlap between normal and abnormal behaviour, but once someone has being labelled as mentally ill, behaviour is interpreted differently.

35 out of 118 of the real patients actually thought that the pseudo-patients were fake and made comments such as - ‘You’re not crazy, you’re a journalist or a professor. You’re checking up on the hospital.’ During their collective stays in hospital 2100 pills were given to the pseudo-patients, with all but two being flushed down the toilet, which went unnoticed. Staff preferred to stay away from the patients - attendants spent an average of 11.3% of their time outside the ‘cage’ (the nickname for staff quarters).

Nurses left the cage 11.5 times per day and 9.4 times per night shift, with doctors only doing so 6.7 times a day on average. Patients’ movements were watched and restricted, their quarters and possessions could be entered and examined by any staff member and notes were available to all members of staff.

There was little personal privacy - some hospitals had no toilet doors, and examinations took place in semi-public rooms. There were also cases of serious physical abuse to patients but these abuses of power stopped in front of other staff. All pseudo-patients reported powerlessness and depersonalisation.

When the pseudo-patients made the request to staff a question the response was either brief while they were ‘on the move’, with head averted, or no response was given at all and staff rarely made eye contact with them. Pseudo-patients were spoken to 4% of the time by a doctor and 0.5% by a nurse, compared to 100% of students in the control group. Interestingly when the student asked where she could find a psychiatrist the response dropped to 78%.

In the follow up experiment, 41 out of 193 patients were judged with high confidence to be pseudo-patients by at least one member of staff, while 23 were judged to be by at least one psychiatrist and 19 by one psychiatrist and one other staff member.

Conclusions

- Rosenhan concludes that diagnosis of mental illness is inaccurate and his view that ‘we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals’ is supported by his findings.

- Mental hospitals seem to exacerbate patients’ difficulties, rather than being helpful, and supportive staff are insensitive.

- The mental health of a patient can be damaged further once a patient is institutionalised.

- Powerlessness and depersonalisation occurs and once someone is labelled with a diagnosis all behaviour is viewed in relation to their label, e.g. ‘Schizophrenia in Remission’.

- This study showed that DSM had poor reliability and the diagnosis of mental illness can be dependent on the situation a person is in.

David Rosenhan

David Rosenhan

Key Study: Rosenhan (1973) Evaluation Points

What are the strengths and weaknesses of the method used in this study?

Field experiments have the advantage of being conducted in a real environment and this gives the research high ecological validity. However it is not possible to have as many controls in place as would be possible in a laboratory experiment. Participant observation allows the collection of highly detailed data without the problem of demand characteristics. As the hospitals did not know of the existence of the pseudo-patients, there is no possibility that the staff could have changed their behaviour because they knew they were being observed. However this does raise serious ethical issues (see below) and there is also the possibility that the presence of the pseudo-patient would change the environment in which they are observing.

Was the sample representative?

Strictly speaking, the sample is the twelve hospitals that were studied. Rosenhan ensured that this included a range of old and new institutions as well as those with different sources of funding. The results revealed little differences between the hospitals it this suggests that it is probably reasonable to generalise from this sample and suggest that the same results would be found in other hospitals.

What type of data was collected in this study?

There is a huge variety of data reported in this study, ranging from the quantitative data detailing how many days each pseudopatient spent in the hospital and how many times pseudopatients were ignored by staff through to qualitative descriptions of the experiences of the pseudopatients. One of the strengths of this study could be seen as the wealth of data that is reported and there is no doubt that the conclusions reached by Rosenhan are well illustrated by the qualitative data that he has included.

Was the study ethical?

Strictly speaking, no. The staff were deceived as they did not know that they were being observed and you need to consider how they might have felt when they discovered the research had taken place. Was the study justified? This is more difficult as there is certainly no other way that the study could have been conducted and you need to consider whether the results justified the deception. This is discussed later under the heading of usefulness.

What does the study suggest about individual / situational explanations of behaviour?

The study suggests that once the patients were labelled, the label stuck. Everything they did or said was interpreted as typical of a schizophrenic (or manic depressive) patient. This means that the situation that the pseudopatients were in had a powerful impact on the way that they were judged. The hospital staff were not able to perceive the pseudopatients in isolation from their label and the fact that they were in a psychiatric hospital and this raises serious doubts about the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnosis.

What does the study tell us about reinforcement and social control?

The implications from the study are that patients in psychiatric hospitals are ‘conditioned’ to behave in certain ways by the environments that they find themselves in. Their behaviour is shaped by the environment (nurses assume that signs of boredom are signs of anxiety for example) and if the environment does not allow them to display ‘normal’ behaviour it will be difficult for them to be seen as normal. Labelling is a powerful form of social control. Once a label has been applied to an individual, everything they do or say will be interpreted in the light of this label.

Rosenhan describes pseudopatients going to flush their medication down the toilet and finding pills already there. This would suggest that so long as the patients were not causing anyone any trouble, very little checks were made.

Was the study useful?

The study was certainly useful in highlighting the ways in which hospital staff interact with patients. There are many suggestions for improved hospital care / staff training that could be made after reading this study. However, it is possible to question some of Rosenhan’s conclusions. If you went to the doctor falsely complaining of severe pains in the region of your appendix and the doctor admitted you to hospital, you could hardly blame the doctor for making a faulty diagnosis. Isn’t it better for psychiatrists to err on the side of caution and admit someone who is not really mentally ill than to send away someone who might be genuinely suffering? This does not fully excuse the length of time that some pseudopatients spent in hospital acting perfectly normally, but it does go some way to supporting the actions of those making the initial diagnosis.

The findings from this study are shocking, in that professional mental health workers were unable to distinguish those who are mentally healthy from those who are mentally ill. Furthermore, the stigma, labelling and treatment of individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental illness was unacceptable. Rosenhan’s research was very useful in improving our understanding of how to treat individuals with mental health problems. We should consider alternatives to hospitalisation, such as psychological treatments and community based therapy which treat the patient as an individual. Furthermore, staff training and education on mental health has improved drastically since the 1970s, with this study being a catalyst for a change in attitudes.

Validity

The study was carried out in 1973 and as a result of Rosenhan’s research, attitudes towards mental health have changed. So although this study was extremely useful, the findings are not representative of mental health care today, so therefore lack historical validity.

Individual/Situational Explanations

Rosenhan suggests that the diagnosis of mental illness is due to situational factors, rather than real symptoms displayed by an individual. The fact that the pseudo-patients were diagnosed with a mental illness, treated and labelled as being in remission despite not showing any symptoms was due to the situation they were in as part of the study. Invalid/inaccurate and unreliable/inconsistent diagnoses are likely to occur depending on the situation/doctor who interprets an individual’s symptoms in relation to the DSM.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of the method used in this study?

Field experiments have the advantage of being conducted in a real environment and this gives the research high ecological validity. However it is not possible to have as many controls in place as would be possible in a laboratory experiment. Participant observation allows the collection of highly detailed data without the problem of demand characteristics. As the hospitals did not know of the existence of the pseudo-patients, there is no possibility that the staff could have changed their behaviour because they knew they were being observed. However this does raise serious ethical issues (see below) and there is also the possibility that the presence of the pseudo-patient would change the environment in which they are observing.

Was the sample representative?

Strictly speaking, the sample is the twelve hospitals that were studied. Rosenhan ensured that this included a range of old and new institutions as well as those with different sources of funding. The results revealed little differences between the hospitals it this suggests that it is probably reasonable to generalise from this sample and suggest that the same results would be found in other hospitals.

What type of data was collected in this study?

There is a huge variety of data reported in this study, ranging from the quantitative data detailing how many days each pseudopatient spent in the hospital and how many times pseudopatients were ignored by staff through to qualitative descriptions of the experiences of the pseudopatients. One of the strengths of this study could be seen as the wealth of data that is reported and there is no doubt that the conclusions reached by Rosenhan are well illustrated by the qualitative data that he has included.

Was the study ethical?

Strictly speaking, no. The staff were deceived as they did not know that they were being observed and you need to consider how they might have felt when they discovered the research had taken place. Was the study justified? This is more difficult as there is certainly no other way that the study could have been conducted and you need to consider whether the results justified the deception. This is discussed later under the heading of usefulness.

What does the study suggest about individual / situational explanations of behaviour?

The study suggests that once the patients were labelled, the label stuck. Everything they did or said was interpreted as typical of a schizophrenic (or manic depressive) patient. This means that the situation that the pseudopatients were in had a powerful impact on the way that they were judged. The hospital staff were not able to perceive the pseudopatients in isolation from their label and the fact that they were in a psychiatric hospital and this raises serious doubts about the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnosis.

What does the study tell us about reinforcement and social control?

The implications from the study are that patients in psychiatric hospitals are ‘conditioned’ to behave in certain ways by the environments that they find themselves in. Their behaviour is shaped by the environment (nurses assume that signs of boredom are signs of anxiety for example) and if the environment does not allow them to display ‘normal’ behaviour it will be difficult for them to be seen as normal. Labelling is a powerful form of social control. Once a label has been applied to an individual, everything they do or say will be interpreted in the light of this label.

Rosenhan describes pseudopatients going to flush their medication down the toilet and finding pills already there. This would suggest that so long as the patients were not causing anyone any trouble, very little checks were made.

Was the study useful?

The study was certainly useful in highlighting the ways in which hospital staff interact with patients. There are many suggestions for improved hospital care / staff training that could be made after reading this study. However, it is possible to question some of Rosenhan’s conclusions. If you went to the doctor falsely complaining of severe pains in the region of your appendix and the doctor admitted you to hospital, you could hardly blame the doctor for making a faulty diagnosis. Isn’t it better for psychiatrists to err on the side of caution and admit someone who is not really mentally ill than to send away someone who might be genuinely suffering? This does not fully excuse the length of time that some pseudopatients spent in hospital acting perfectly normally, but it does go some way to supporting the actions of those making the initial diagnosis.

The findings from this study are shocking, in that professional mental health workers were unable to distinguish those who are mentally healthy from those who are mentally ill. Furthermore, the stigma, labelling and treatment of individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental illness was unacceptable. Rosenhan’s research was very useful in improving our understanding of how to treat individuals with mental health problems. We should consider alternatives to hospitalisation, such as psychological treatments and community based therapy which treat the patient as an individual. Furthermore, staff training and education on mental health has improved drastically since the 1970s, with this study being a catalyst for a change in attitudes.

Validity

The study was carried out in 1973 and as a result of Rosenhan’s research, attitudes towards mental health have changed. So although this study was extremely useful, the findings are not representative of mental health care today, so therefore lack historical validity.

Individual/Situational Explanations

Rosenhan suggests that the diagnosis of mental illness is due to situational factors, rather than real symptoms displayed by an individual. The fact that the pseudo-patients were diagnosed with a mental illness, treated and labelled as being in remission despite not showing any symptoms was due to the situation they were in as part of the study. Invalid/inaccurate and unreliable/inconsistent diagnoses are likely to occur depending on the situation/doctor who interprets an individual’s symptoms in relation to the DSM.