Mary Ainsworth

Mary Ainsworth

Background: The development of attachment and impact of the failure to develop attachments

Key Study: Ainsworth & Bell (1982)

Application: Develop an attachment friendly environment.

Key Study: Ainsworth & Bell (1982)

Application: Develop an attachment friendly environment.

Background: What is attachment?

Background: The evolutionary theory of attachment

Background: Types of attachment

Background: Stages of attachment

Background: Short-term effects of failed attachments

Background: The impact of long-term failed attachments

Background: Attachment deprivation

- An attachment is a close social bond that is formed between one person and another person.

- Research has tended to focus on the child–mother attachment as the main carer.

- There are many reasons why a newborn baby would want to create a close attachment with a carer immediately.

- Behaviourists believe that all people are born as blank slates and our behaviour is formed solely by which behaviours are reinforced or punished.

- Babies learn to become attached to their carer as the carer provides them with positive reinforcement for their actions.

- For example, when a baby cries, the carer will try to put right whatever has gone wrong.

- A carer is the primary feeder for the baby.

- A carer plays with the baby and makes them laugh.

- A carer helps remove unpleasant feelings (e.g. a wet nappy).

- All but one of these examples are positive reinforcement. (Which example is negative reinforcement?)

- Behaviourists would argue that the attachment between carer and baby is formed through simply association and positive reinforcement.

Background: The evolutionary theory of attachment

- John Bowlby proposed that forming an attachment is an evolutionary mechanism that helps to ensure the survival of a newborn baby.

- He suggested that this need to form an attachment is biological and innate, rather than learned like the behaviourist theory.

- The carer also has an innate response to form an attachment as they will feel the need to respond to babies’ cries and smiles on an innate, pre-programmed level.

- Some research has supported this idea: Bushnell et al. (2011) found that newborn babies can almost immediately recognise their mother.

- MRI scans of mothers’ brains have also shown that certain areas of the brain respond to their own baby’s cries, but not other babies – suggesting an innate response.

Background: Types of attachment

- There are four types of attachment that can be formed:

- Secure – The parent is caring and loving, leading to the child seeing closeness with the caregiver.

- Insecure avoidant – The parent becomes annoyed and may resort to rejecting the child, resulting in that child avoiding the care giver in times of need.

- Insecure resistant – The parent is insensitive and prone to mood swings leading to overreactions or putting themselves before the child. This could lead the child to exaggerate their own problems to make sure the parent responds.

- Insecure disorganised – The parent is frightening, abusive (physically, verbally or sexually) and insensitive to the child. The parent can be neglectful (degrading and pushing away the child) and withdrawn, making communication errors (e.g. laughing at child’s distress). This may lead to the child either running from the parent or freezing on the spot and growing up with emotional and social problems (Main and Solomon 1986).

Background: Stages of attachment

- The attachment between carer and child does not appear immediately but develops steadily.

- Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson (1964) studied 60 babies over 18 months. Through observations between the carer and child, as well as the child on their own, they identified four stages in which an attachment develops:

- Indiscriminate attachments – Up to 3 months old babies will respond equally to anyone that gives them care.

- Specific attachments – After 4 months the baby will still accept care from anyone but will recognise primary and secondary caregivers.

- Single attachment figure – The baby after 7 months now looks to a person as a source of care and will show fear and unhappiness when separated from them.

- Multiple attachments – After 9 months the baby is more independent and forms several attachments with adults who they have spent significant time with.

- Schaffer and Emerson state that the attachment figure doesn’t have to be with the mother but any significant caregiver who can respond best with what the baby needs (sensitive responsiveness).

- The cognitive approach could also help explain how attachment develops – once the baby has achieved object permanence, they will understand that their carer still exists even when they cannot see them and the acquisition of language helps the child understand when the parent will be there and won’t be there (e.g. at work) which helps them to be away from their carer for short periods.

Background: Short-term effects of failed attachments

- Some research suggests separating a child from the carer for a short time can have negative effects.

- The Robertsons filmed what happened to children in hospital care between 17 months and 3 years. In this time their mothers would leave for periods up to 2 weeks at a time (in 1948 parents were discouraged from visiting their children for too long).

- The Robertsons identified three stages of short-term deprivation:

- Distress – The child will protest, cry and become angry when the carer leaves. This can last for days.

- Despair – When the child realises the carer is not coming back they become quiet and just sit, maybe with a cuddly toy.

- Detachment – The child would still be upset but would now ignore the carer and try to get away from them.

Background: The impact of long-term failed attachments

- If the short-term effects of attachment are negative, then what will happen to children who spend significant time away from their carers?

- Bowlby (1944) interviewed 44 juvenile criminals (thieves) who were at a guidance clinic as well as their parents.

- Participants were given assessments on intelligence, emotional attitude and psychiatric history.

- Bowlby found several had a lack of affection for others, lacked feelings of guilt and shame as well as empathy for their victims. He called this ‘affectionless psychopathy’.

- Looking at the backgrounds of the criminals he saw some proportion of them (14) had been separated from their mothers at some point.

- He concluded that the reason for this affectionless psychopathy was due to their lack of attachment with their mothers.

Background: Attachment deprivation

- Bowlby suggested no child should be separated from their mother (even for day care or nurseries) as it would cause problems later in life.

- He also stated that there was a ‘critical period’ where attachments had to be formed successfully.

- Spitz and Wolfe (1946) found that children who had been raised in orphanages showed more symptoms of depression than other children, seemingly supporting this deprivation hypothesis.

- However, not all research confirms Bowlby’s ideas. Hodges and Tizard (1989) researched children from a children’s home who were either adopted or returned to their biological parents at the age of 4. They found that it was actually the adopted parents who were better at forming attachments – rejecting Bowlby’s significance of the biological mother.

- However, the institutionalised children still had long-term effects such as bullying, having fewer friends and fewer positive relationships with their siblings.

|

Find out your own attachment style using the online quiz here

|

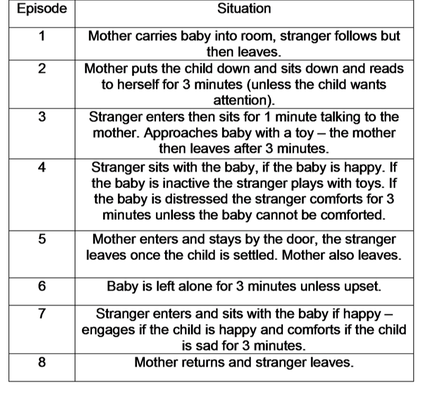

Aim = To observe the attachment behaviours of a child using a ‘strange situation’ in a lab.

Procedure

Episode 1 = Mother carries baby into room, stranger follows but then leaves.

Episode 2 = Mother puts the child down and sits down and reads to herself for 3 minutes (unless the child wants attention).

Episode 3 = Stranger enters then sits for 1 minute talking to the mother. Approaches baby with a toy – the mother then leaves after 3 minutes.

Episode 4 = Stranger sits with the baby, if the baby is happy. If the baby is inactive the stranger plays with toys. If the baby is distressed the stranger comforts for 3 minutes unless the baby cannot be comforted.

Episode 5 = Mother enters and stays by the door, the stranger leaves once the child is settled. Mother also leaves.

Episode 6 = Baby is left alone for 3 minutes unless upset.

Episode 7 = Stranger enters and sits with the baby if happy – engages if the child is happy and comforts if the child is sad for 3 minutes.

Episode 8 = Mother returns and stranger leaves.

Observations

Throughout this the child is observed every 15 seconds through a one-way mirror in the room. Certain behaviours were watched for and scored for strength, frequency and duration.

Results

Discussion

Procedure

- Each child was tested individually.

- They were placed in a square room (9ft by 9ft).

- At one end of the room was a child’s chair surrounded by toys. At the other end was a chair for the mother. Near the door was a chair for a stranger.

- The child was put in the room and left to play freely.

- The ‘strange situation’ then plays out in seven distinct episodes.

Episode 1 = Mother carries baby into room, stranger follows but then leaves.

Episode 2 = Mother puts the child down and sits down and reads to herself for 3 minutes (unless the child wants attention).

Episode 3 = Stranger enters then sits for 1 minute talking to the mother. Approaches baby with a toy – the mother then leaves after 3 minutes.

Episode 4 = Stranger sits with the baby, if the baby is happy. If the baby is inactive the stranger plays with toys. If the baby is distressed the stranger comforts for 3 minutes unless the baby cannot be comforted.

Episode 5 = Mother enters and stays by the door, the stranger leaves once the child is settled. Mother also leaves.

Episode 6 = Baby is left alone for 3 minutes unless upset.

Episode 7 = Stranger enters and sits with the baby if happy – engages if the child is happy and comforts if the child is sad for 3 minutes.

Episode 8 = Mother returns and stranger leaves.

Observations

Throughout this the child is observed every 15 seconds through a one-way mirror in the room. Certain behaviours were watched for and scored for strength, frequency and duration.

- Contact-seeking behaviours – Crying at people, sitting on lap, the proximity to the adults.

- Contact-maintaining behaviours – Clinging, hugging, protesting if released.

- Interaction -voiding behaviours – Ignoring adults, moving away from them.

- Interaction-resisting behaviours – Pushing away adults, screaming.

- Searching behaviours for adults.

- Following mother to the door and going to mother’s empty chair (when she wasn’t in the room).

- Exploratory behaviours – Exploring the room, looking around, playing with toys.

Results

- Exploratory behaviour = Decreased in the stranger’s presence compared to the mother. But also decreased when the mother played with the child.

- Crying = Minimal crying when the stranger was there. Crying happened when the mother left and stopped when the mother came back. Crying again when the mother leaves again and continues even when the stranger comes in.

- Search behaviour = Moderate when the mother was present. Slightly more when the stranger was present. Most often when alone.

- Contact-maintaining behaviour = Shown most often for the mother (when she returned). Occasionally shown to strangers but less often.

- Contact-resisting behaviours = Most did not show this. When shown it was after the mother returned and increased with each separation (half showed it at episode 8). Less of this behaviour towards the stranger.

Discussion

- Children explored at first but once the mother left and returned showed less exploration (clinging onto her).

- When the mother was gone there were more contact-seeking behaviours which continued when she came back and never returned to their original levels.

- The effects of the separation (the distress and despair) lasted longer than the separation happened for. Similar findings with animals have also shown this.

- The reason for avoiding the stranger could simply be fear of the unknown, however, avoiding the mother could be due to detachment of the carer.

Hodder Education's

Psychology Review Centre Spread on the Strange Situation can be found here |

| ||||||

Application: Strategies to develop an attachment friendly environment

Managing separation

When the carer can’t be there

Managing separation

- We know from research that separation from an attachment can have short- and long-term effects.

- When the Robertsons did their research on short-term separation, hospitals kept parents from visiting their children except for two days a week (as it was believed that constant contact would upset the child).

- In modern times the parents are kept close by as much as possible, with hospital beds even made available at home so as to minimise the separation time.

- In times where this is not possible, steps can be taken to ensure there is accommodation available nearby for the parents, siblings and other figures of attachment.

When the carer can’t be there

- In situations where the child will be spending significant time on their own (such as childcare) steps can still be taken to ensure there is attachment.

- Supplementary attachment figures such as nursery staff can make attachments with a small number of children. This can be done beforehand by the staff member reading a personality profile of likes, dislikes and other things relevant to the child. This allows for a unique individualised approach and will allow the worker to provide emotional and physical comfort.

- Key workers like nurses could be on hand to help the child say goodbye to the parents to help ease the separation, which would reduce the negative impacts that separation from attachment figures can bring.

|

An article from The Conversation reviewing parenting practices from around the world can be found here

|